Il Volume 109, Number S1 | December 2018 della prestigiosa rivista Isis. A Journal of the History of Science Society ha pubblicato un breve saggio di Francesco Luzzini, introduttivo alla «Current Bibliography of the History of Science and its cultural influences 2018».

Luzzini analizza e descrive senza infingimenti il danno che le normative e le procedure dell’Anvur (Agenzia Nazionale di Valutazione del sistema Universitario e della Ricerca) hanno inferto in Italia alla ricerca e alla sua diffusione, soffermandosi in particolare, ma non solo, sulla separazione tra riviste scientifiche ‘normali’ e riviste di fascia A, distinzione per la quale il valore di un testo non dipende dal suo contenuto ma dalla sede che lo pubblica; sul peso dato al fattore quantitativo rispetto alla qualità delle indagini, delle ricerche e dei risultati conseguiti; sull’eccessiva importanza attribuita agli articoli di rivista rispetto alle monografie, che sono invece ed evidentemente fondamentali nell’ambito delle scienze umane; sul disconoscimento dell’impegno e del tempo necessari per un’autentica qualità della ricerca -edizioni critiche e monografie richiedono anni di lavoro-, a favore di pratiche frenetiche di scrittura i cui risultati rimangono spesso conformisti nell’approccio e superficiali negli esiti.

Le contraddizioni, le assurdità, le scorrettezze dell’Anvur e di molti accademici emergono da questo testo con inesorabile lucidità. Luzzini scrive tra l’altro:

«A surprisingly large amount of brilliant, rigorous, and innovative research comes from publications that are deemed marginal—or are not considered at all— by the milieu of Italian academia» (p. 4)

«Quantitative assessments and the use of absurdly rigid disciplinary boundaries are detrimental to interdisciplinary research and to those fields, such as the humanities, that should be evaluated on a qualitative basis. Actually, the metrics frenzy is not just an Italian problem, but a global one» (p. 10).

«In any case, this system has had a deleterious effect on scholarly careers and scholarship alike. In the humanities, including the history of science, the combination of quantitative assessment criteria and academic cronyism has continued to distort the way publications are perceived and valued in Italy. In fact, journal articles (especially those published in “Class-A” journals) are far more important in the eyes of ANVUR than other research products such as, say, book chapters or conference proceedings; and this is true regardless of their quality.

The bibliographical implications of this phenomenon are as clear as they are unsettling. There are, of course, many philosophical and historical journals in Italy that contain excellent research work. However, publishing an essay in a high-ranked journal does not necessarily make it good—especially in a context like Italian academia, where clientelism and nepotism are rampant» (p. 11).

«The preparation of a critical edition is a time-consuming and energy-draining endeavor that requires years of interdisciplinary training and philological, linguistic, historical, and scientific research, and—last but not least—a relatively stable academic position. And yet, since the distorting effects of the assessment parameters introduced by ANVUR make works such as monographs or critical editions no more important than articles published in “Class-A” journals, few young scholars invest their time and energies in wearying, difficult, and (academically) unrewarding long-term projects, despite the high scholarly merit that these projects produce» (p. 12)

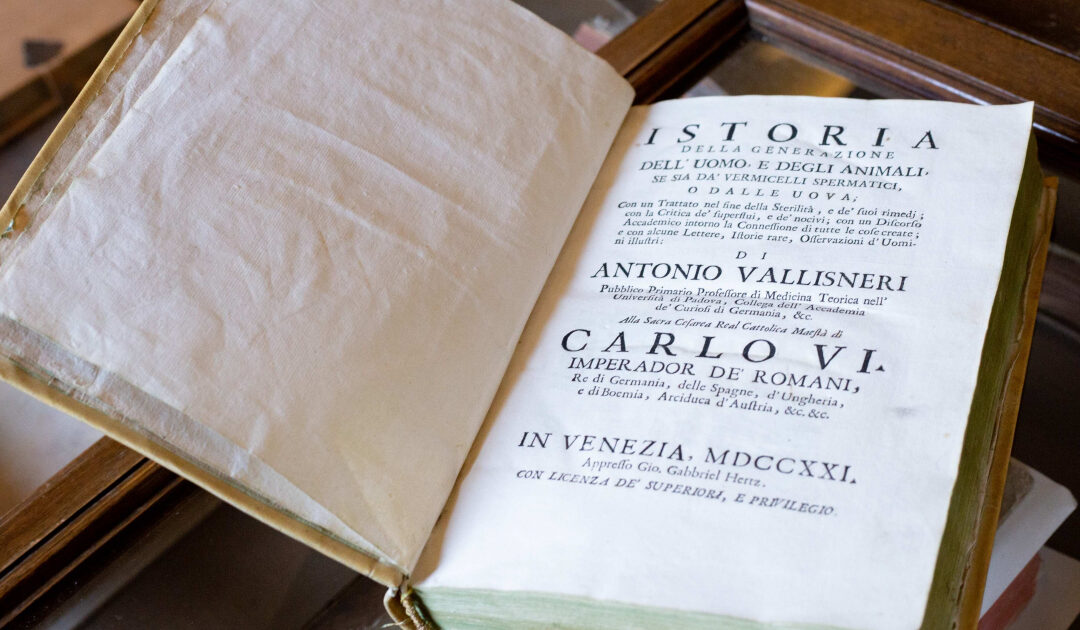

Luzzini offre inoltre un resoconto delle migliori opere di storia della scienza pubblicate di recente in Italia. Tra queste emerge l’Edizione Nazionale delle Opere di Antonio Vallisneri coordinata da Dario Generali, e altre opere di questo studioso che è ormai tra i più prestigiosi storici della scienza in Europa, i cui lavori -suoi personali e quelli del gruppo di ricerca che intorno a lui si raccoglie– costituiscono un prezioso patrimonio per chiunque voglia comprendere la genesi, le dinamiche e i risultati delle scienze della vita in età moderna. E questo conferma che «light and shadow have intertwined to form a contradictory and entangled pattern of quality and mediocrity, and this often makes it difficult to keep good and bad scholarship apart» (p. 13).

Consiglio quindi la lettura integrale del saggio, che può essere liberamente scaricato dal sito della Rivista pubblicata dall’Università di Chicago: Bibliographical Distortions, Distortive Habits: Contextualizing Italian Publications in the History of Science.

[Photo by Patrick Robert Doyle on Unsplash]